site search

online catalog

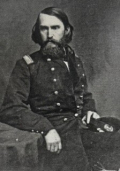

SIGNIFICANT INSCRIBED PRESENTATION SWORD OF COL. JOHN C. WALKER, 1st IRISH AND 35th INDIANA, SUMMARILY DISCHARGED AND A CONSPIRATOR IN THE 1864 PLANNED UPRISING IN INDIANA BY THE “SONS OF LIBERTY”

$3,750.00 SOLD

Quantity Available: None

Item Code: 2024-274

This attractive presentation sword was given to Colonel John Crawford Walker by the “officers of his corps,” the 35th Indiana, also known as the “First Irish.” The presentation is patriotically dated July 4, 1862, but is also a gesture of support to their colonel in a power struggle with Indiana Governor O.P. Morton over his insistence on determining promotions among his officers, supposedly to preserve their seniority over officers transferred into the regiment by Morton as part of the effort to consolidate understrength units. It twice ended badly for Walker, who was both a political opponent of the Governor and regarded the regiment as his own domain: once with his summary discharge from the service, and again with his hasty exit to England in 1864 when his role in the “Sons of Liberty” conspiracy to overthrow the Governor and take the state out of the war and possibly out of the Union was unmasked.

The gilt brass guard preserves lots of its bright color, the wire binding of the grip only showing a tad darker from handling. The pommel cap is fairly wide with a border of thirteen raised, five-pointed stars on a stippled ground. In the center is an oval mother-of-pearl panel in a beaded border, decorated with an incised band of floral elements, running lengthwise, with upper and lower border lines with raised, lined triangles pointing toward the beaded edge. The plaque shows a very narrow hairline crack, but is stable and there are no chips. The edge of the brim is cast and chased with small floral motifs. The face of the pommel has a second mother of pearl panel with beaded edge showing a US eagle standing upright, with more floral motifs along the bottom. The knucklebow is flat, splits off to the obverse with two branches, the outer one branching again to form a loop back to the middle branch, which also loops back to the knucklebow, with the open space above filled by the Arms of the US- an eagle with shield on its chest, E Pluribus Unum ribbon, etc. This is framed above by the outer branch that curls inward to join the narrow crossguard that extends up to the quillon. The knucklebow also splits off into one side branch on the reverse that has a secondary branch curving up the crossguard and ends in a loop curving down, in effect producing an oval side loop for the guard. The outermost branches on the obverse and reverse are cast and chased with shallow floral motifs. The grip is wrapped in black leather and bound with a single strand of thick gilt brass wire. The leather pad at the blade shoulder is present. The wire binding shows as a medium brass patina from handling. The leather wrap has good color and surface showing just some small wear spots.

The blade is bright with only a few, very small gray spots and the etching is vivid. In form the blade follows the regulations in being slightly curved with single edge though it has an unstopped main fuller and narrow upper fuller running under the back edge until is changes to a false edge with the blade forming a spearpoint tip. The edge and point are good. The blade is etched on both sides. The obverse uses a United States shield at the ricasso, with leafy vines in the upper and lower panels and an eagle framed in the middle, with outstretched wings, clutching arrows and olive branch, with some jagged arrowhead lightning bolts jutting out from underneath its wings and an “E PLURIBUS UNUM” ribbon scroll entwined with floral motifs forward of this. The reverse uses similar motifs, but with the shield left blank, likely for a retailer’s address, and the leafy vines extend to frame a block letter “U.S.” as the central panel, with the U.S. having its own floral spray terminals and following it with a small wreath, tied with a ribbon, before the second panel of scrolling, leafy vine.

The scabbard is gilt brass, matching the hilt in color with just some rubbing to the finish from handling below the throat, lower ring mount and on the drag. There are no dents, dings, or breaks. The scabbard is fitted with throat, both ring bands with mounts and the drag, all plain on the reverse, but with the latter three showing wreathes in relief on the obverse, with the ring bands cast and chased with floral elements on both sides. On the obverse between the ring mounts the scabbard is engraved in a mix of script and Old English lettering: “Presented to / Col. J.C. Walker, / 1st Irish. 35th Regt. Ind. Vol. / by the Officers of his corps, / Fayetteville. Tenn. July 4th 1862.” This presentation is mirrored by a finely punch-dotted inscription inside the guard, “COL. J.C. WALKER / FROM THE OFFICERS OF HIS / CORPS / 1862."

Walker was born in 1828 in Indiana, the son of a prominent and wealthy Democratic state senator, but was himself frustrated in his quest for political power. He made a name for himself in publishing and editing party newspapers, but served only one term in the state house of representatives before being defeated and in the 1856 had to withdraw his candidacy for lieutenant governor because he was underage, only to watch his replacement not only win election, but briefly become Governor when the head of the ticket died in office in 1860.

Elections in 1860 brought new Republican Lieutenant Governor Oliver P. Morton into the Governor’s office when the war began and Governor Lane took a military command in 1861. As a purported “war Democrat” Walker vainly proposed raising a cavalry regiment, but finally succeeded in getting Morton’s authorization to raise an infantry regiment, likely an attempt by Morton to build a united front in the state. Eventually designated the 35th Indiana, the regiment was informally known as the “First Irish,” hoping to recruit from that ethnic community, relying on the background of his Lieutenant Colonel and many of his officers. Enrolling officially August 14, 1861, he was commissioned Colonel by Governor Morton dating to the regiment’s muster into service on Dec. 11, 1861. The regiment left the state December 13 for Bardstown, KY, and six weeks later joined Buell’s forces at Bowling Green and then moved into Tennessee.

Walker almost immediately proved a headache for Morton in his effort to play favorites among his officers. When the regiment’s Lt. Colonel left under a cloud in early 1862 Walker favored J.C. Hughes, who had been commissioned a captain to raise a company for the regiment but failed to do so and thus was never mustered in, but tagged along hoping something would turn up. Walker then took it as a “personal insult” when Morton promoted the regiment’s Major to the post, even withholding the new commission for ten days and then advising the Major not to accept it, eventually leading to that officer’s resignation from the regiment. In June Walker’s antipathy for the Governor was again roused when in accordance with official policy of consolidating understrength regiments the Governor folded the 61st Indiana, called by some the “2nd Irish, into the 35th and issued new commissions to transferred officers to fill vacancies in the 35th (including the post of Lieutenant Colonel.) This came to a head on June 18, when the transferred officers and men reported to Walker at “Camp Cooper, Tenn.” and with the sole exception of an Assistant Surgeon, Walker refused to accept the officers even though, as the new Lt. Colonel correctly pointed out, the consolidation had come down in official orders, his commission derived from the same authority as Walker’s, and that Walker had no “right to either accept or decline” his services. The whole mess boiled over into communications up and down the army chain of command and between Morton and Gen. Halleck through June and July, with Walker, realizing he had overreached, maintaining that he had been trying to prevent outsiders from being ranked over his “veterans” and keep his own officers from resigning in protest. The sword, of course, would offer some evidence for his officers’ support of his position, but one cannot help thinking there was a lot of mutual backscratching and personal aggrandizement going on in the regiment’s officer corps rather than concern for the good of the service. Morton apparently thought so, too, and obtained orders for Walker’s arrest. Whether that was carried out is unclear. Walker kept busy writing protests and explanations and then managed to get a thirty-sick leave to go home and lie low, and was apparently surprised to receive notice of his discharge on August 6.

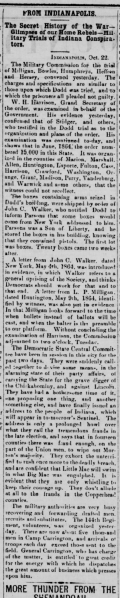

That did not end his campaign for reinstatement or a court of inquiry, or his vendetta against Morton. With election of a Democratic legislature in 1862, Walker was appointed state agent in New York and immediately went to work sabotaging the state’s credit in raising funds for the war effort. Morton found a work-around in using his own credit, a private loan, and federal funds to keep things going, but Walker was also involved in a network of secret organizations known successively as “Knights of the Golden Circle,” “Order of American Knights,” and “Sons of Liberty,” conspiring not only to take the state out of the war, but even out of the Union and aid the Confederacy by freeing Confederate POWs and seizing a federal armory. The date of a purported actual uprising was several times postponed, however, and Morton was able to unmask the conspiracy and arrest its various actors. One of the key physical pieces of evidence of their intentions was 400 revolvers in the possession of Harrison H. Dodd, one of the principal leaders, shipped to him from New York in boxes marked “Bibles” by Walker, who reportedly held the rank of “Major General” in the organization with command of one of the “divisions” into which they had divided the state. The other conspirators found themselves in front of military tribunals; Walker decided England had better climate; and, the state legislature swung back into the Republican camp.

The conspirators ended were eventually released in 1866 with the war fever over and the supreme court finding fault with their trials before military tribunals. Walker himself cooled his heels in England until 1873, when he returned with a pardon from Andrew Johnson in his pocket, a new wife, three children, and a medical education, which he continued at Indiana Medical College, and put into practice in Shelbyville, IN, until 1879 when he was appointed assistant physician at the Hospital for the Insane at Indianapolis, a post in which he died 1883.

Not all officers can be heroes, we suppose, but for his involvement in prewar and wartime politics, internal army power struggles, personal vendettas, a bit of treason, and a supreme court decision (“ex parte Milligan”) this sword is hard to beat. [sr][ph:L]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

THIS ITEM, AS WITH ALL OTHER ITEMS AVAILABLE ON OUR WEB SITE,

MAY BE PURCHASED THROUGH OUR LAYAWAY PROGRAM.

CLICK HERE FOR OUR POLICIES AND TERMS.

THANK YOU!

Inquire About SIGNIFICANT INSCRIBED PRESENTATION SWORD OF COL. JOHN C. WALKER, 1st IRISH AND 35th INDIANA, SUMMARILY DISCHARGED AND A CONSPIRATOR IN THE 1864 PLANNED UPRISING IN INDIANA BY THE “SONS OF LIBERTY”

For inquiries, please email us at [email protected]

Most Popular

Historical Firearms Stolen From The National Civil War Museum In Harrisburg, Pa »

Theft From Gravesite Of Gen. John Reynolds »

Selection Of Unframed Prints By Don Troiani »

Fine Condition Brass Infantry Bugle Insignia »

Wonderful Condition Original Confederate-Manufactured Kepi For A Drummer Boy Or Child »

featured item

CONFEDERATE GENERAL THOMAS “STONEWALL” JACKSON’S SIGNED, PERSONAL COPY OF A COMPLETE TREATISE ON FIELD FORTIFICATIONS

Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson Signed Copy of His West Point Textbook, A Complete Treatise on Field Fortifications. The future Confederate general's bold signature, signed "Thos. J. Jackson" ca. 1846, occurs at the top of the front free endpaper. The… (1179-682). Learn More »

site search

Upcoming Events

The shop will remain closed to the public through Friday, Jan. 31st, re-opening on Saturday, Feb.… Learn More »