site search

online catalog

REMARKABLE LETTER GROUP – CHARLES FISHER, 36th MASSACHUSETTS – DIED OF DISEASE

$975.00 SOLD

Quantity Available: None

Item Code: 2024-2086

Charles B. Fisher was but 22 years old when he enlisted on August 7, 1862 as a Sergeant in Company D of the 36th Massachusetts Infantry. Prior to his volunteer service, Charles was a mechanic in Templeton, Massachusetts. After the regiment was mustered in, they were moved to Washington, D.C. and then moved again to cover the Pleasant Valley area of Maryland with the rest of the 9th Corps during Lee’s invasion of 1862. Though not engaged in the Battles of South Mountain or Antietam, Charles writes his first letter in October from Pleasant Valley, detailing recent service near Point of Rocks, and to lament that he and the rest of the men are not always treated well by the officers. He does mention that they have not experienced most of the hardships of other units yet.

From there, the regiment marched to Lovettsville, Virginia and then on to Warrenton. Several of his letters were written from Fredericksburg and include much detail of the preparations for the famous fight. He details the “rebels” positions in the city opposite his position, and describes General Burnside’s plans to erect the pontoon bridges and move no less than 100,000 men against the downtown area and the lines beyond. Charley, as he sometimes called himself, said that Burnside will “fight the world” and hoped that the army would not make any mistakes that would prevent them from moving to take Richmond after the fall of Fredericksburg. On December 18th, Charley describes observing much of the action while supporting a battery as his division was spared from the bloody assaults. He mentions two family friends from Massachusetts being wounded while in service with the 21st Mass., losing 5 men of the regiment, and how they will likely stay in place unless “they wish to kill off all the men fer nothing.”

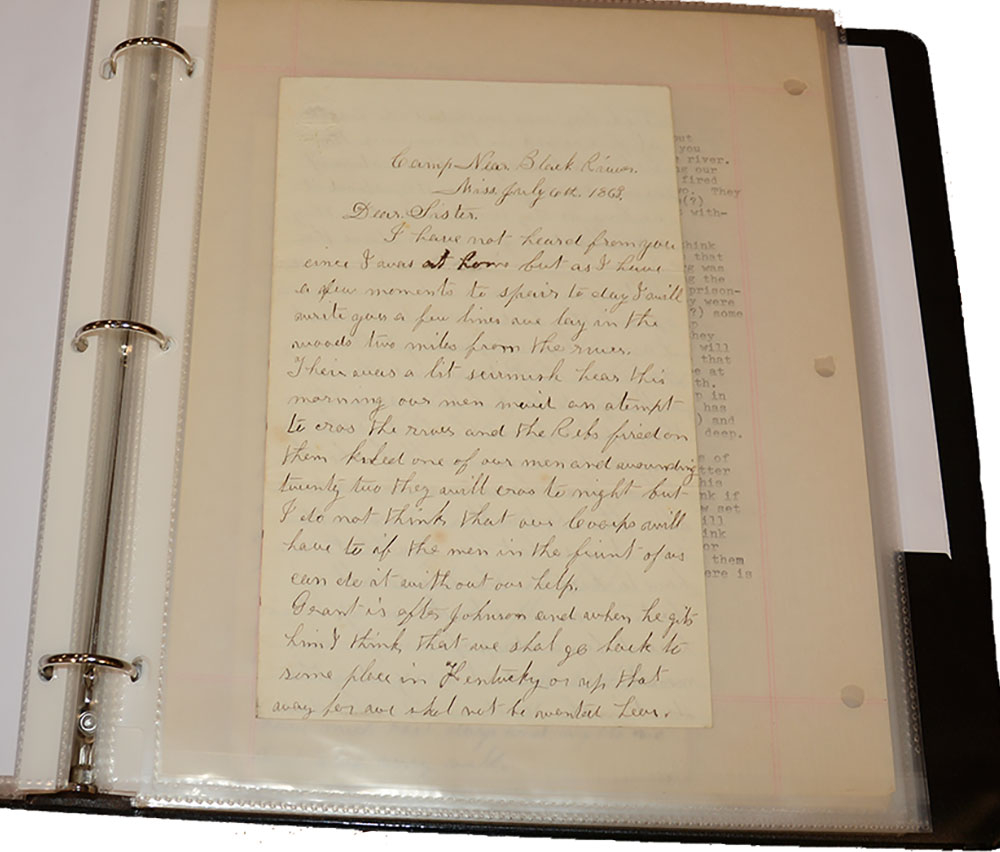

It's from Wind Mill Point, Virginia, that Charley talks of the “Mud March” and laments the state of the men, detailing that they were growing sick in increasing numbers, and dying at a rate that required multiple daily burials. By June of 1863, Charley neared Vicksburg on a troop transport ship. As they passed Greenville, Charley mentions taking enemy fire and returning it in kind. Though he does not have much direct knowledge of the casualty figures, he makes a point to say that several of his mates saw a US cannon round strike a ‘rebel’ and tear him in two, while no one on his ‘boat’ was hit. Obviously anxious about the sporadic violent hostility, he said that if enemy fire does not stop coming from houses along the river, the homes and towns will be burned and destroyed by the Navy. In this same letter, he relates a humorous story about a picket detail being “driven in” by a cow moving through the dark underbrush on a bank of the Mississippi River. In subsequent letters, he mentions former slaves coming into the regiment’s lines and willing to work on entrenchments for protection and housing while the heavy guns echo from the constant shelling of Vicksburg. Word had also reached him that Lee was moving into Pennsylvania and wished the Army of the Potomac could have General Grant instead of General Hooker. On July 6th, Charley makes a brief account of a fight with the enemy in which one man is killed and twenty-two wounded while trying to cross the river south of Vicksburg.

After being sent to Kentucky, Charley notes that an increasing number of men are getting sick – up to 60 by his count in early August. By late August, his letters originate from the Seminary Hospital in Covington, Kentucky, where he has taken ill with a mystery virus or infection. He said he was unable to sit upright or move about for 9 days prior to his first accounting from the hospital. His letters begin to strike a less hopeful tone as his health fails to improve. A fellow Sergeant, Francis Perry of Company D, took it upon himself to write Charley’s father. Candidly, he details Charley’s poor condition and that he was given a watch and photographs from Charley to pass along if he does not survive his illness. In this rather human letter, Francis talked about doing his best to keep Charley’s spirits up, but also stated that Charley would likely die without more advanced medical assistance. One last letter from Charley exhibits a glimmer of hope that his condition is improving, following a letter from Francis detailing his friend’s final days and hours prior to passing away. He said Charley did not wish to burden his family or friends with the task of visiting him and that he wished for Charley’s “lady” to know that he spoke of her often, was always ready to do his duty, and was well liked by the men.

The next documents in the grouping are a letter and telegraph messages from Charley’s father to his wife updating her on the retrieval of their son’s body, followed by a pay requisition form post-dating the war, a pension claim filed by Charley’s mother, and several pension approval documents and pay records. Several family letters, and various newspaper clippings are also included, along with a recent photo of Charles’ headstone in Massachusetts.

The grouping includes 15 letters written by Charles, 2 written by Francis, 1 letter from Charles’ father, 2 telegrams concerning the retrieval of the body, 4 pension related and pay documents, a letter detailing the on-hand family money in the 1890’s, an 1893 receipt or bill from a hotel stay, a request form for the addresses of family of deceased soldiers, and 3 newspaper clippings – one a poem about General Sheridan and a visit to Massachusetts in 1867, and the others concerning pension laws from 1883. All letters, with the exception of the included civilian family letters, have been transcribed in full. All documents and letters are housed in protective sleeves and joined by a 3-ring binder. Also included are a regimental history, a copy of Charles’ service record, and archival copies of assorted service documents.

This grouping tells the emotional story of a young man who lost his life in service of his country in his own words. Together, each letter and document offers a stirring portrait of a non-commissioned officer’s trials and experiences in multiple theatres of the war, and the pain his loved ones endured after his death. This grouping would surely be a feature of any Civil War collection. [cm][ph:L]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

THIS ITEM, AS WITH ALL OTHER ITEMS AVAILABLE ON OUR WEB SITE,

MAY BE PURCHASED THROUGH OUR LAYAWAY PROGRAM.

CLICK HERE FOR OUR POLICIES AND TERMS.

THANK YOU!

Inquire About REMARKABLE LETTER GROUP – CHARLES FISHER, 36th MASSACHUSETTS – DIED OF DISEASE

For inquiries, please email us at [email protected]

Most Popular

Historical Firearms Stolen From The National Civil War Museum In Harrisburg, Pa »

Theft From Gravesite Of Gen. John Reynolds »

Selection Of Unframed Prints By Don Troiani »

Fine Condition Brass Infantry Bugle Insignia »

British Imported, Confederate Used Bayonet »

Scarce New Model 1865 Sharps Still In Percussion Near Factory New »

featured item

BREVET MAJOR GENERAL’S COMMISSION AND G.A.R. BADGE OF SAMUEL SPRIGG CARROLL: HIS TROOPS HELPED SAVE CEMETERY HILL ON JULY 2 AND TO REPULSE PICKETT ON JULY 3 AT GETTYSBURG

Carroll was a fighting general who acquired several nicknames from his red hair along with three wounds and a number of promotions and brevets for his service on the battlefield. He received several brevets for actions in individual battles: major… (2020-894). Learn More »

site search

Upcoming Events

May 16 - 18: N-SSA Spring Nationals, Fort Shenandoah, Winchester, VA Learn More »